Trees: The Miracle Municipal Asset

Article written by: Michael Rosen R.P.F., President of Tree Canada & James Lane R.P.F., Manager and Natural Heritage & Forestry at the Regional Municipality of York.

Article published in: Municipal World

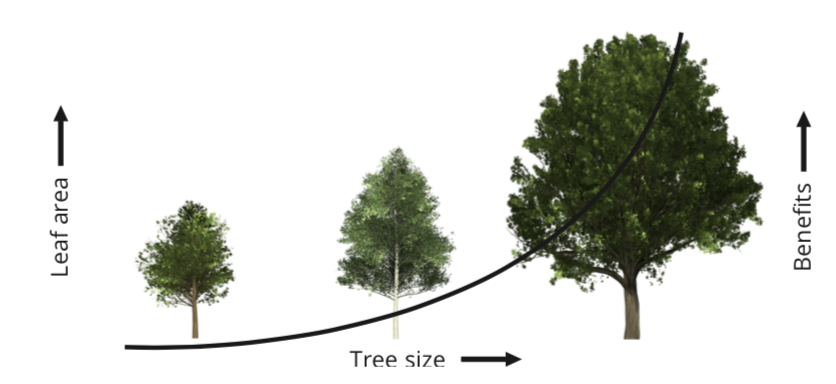

For municipal asset managers, the assumption is always made that assets will devalue with time. Sidewalks crumble, roads pothole, and bridges need replacing. So says the asset manager as they put forward the various arguments to their line managers for the budget to provide for maintenance or replacement. Yet no matter which way you look at it, trees only increase in value. Not only that, but the value they provide – whether it be economic (e.g., property value), environmental (e.g., CO2 capture), or health (e.g., psychological well-being) – increases exponentially with time and size. This article will discuss the value of trees as a municipal asset, with some measurement examples drawn from the experience in York Region.

Historic Context

The perception of trees has changed with time in Canada, especially within the municipal context. Indigenous societies lived with trees, using them for medicine, fuel, and shelter while understanding their function in wildlife habitat. While trees were cleared by some First Nations for agricultural production, European colonization brought an entirely different set of values (and scale) to the clearing of forests and trees. Indeed, trees were frequently seen as a hindrance to “development” and “civilization” and were frequently seen as something to “get rid of”. In later centuries, trees were increasingly valued for their timber properties and in the municipal context, trees were felled to make way for “progress”. In the case of the famous “Cary Fir” in the early part of the 20th century in North Vancouver, British Columbia, municipal officials and citizens celebrated with great enthusiasm as the huge mammoth Douglas fir was felled to make way for “civilization”. Such reactions would be inconceivable today.

Indeed, it was not until later in the 20th century that municipalities sought to “manage” the trees within their jurisdiction. As the industrial revolution made possible the concept of “leisure time”, citizens began to demand that their parks (and trees) provide them with recreational opportunities and beauty as a respite from their hard- working lives. Cities complied. Most of the great iconic Canadian urban parks (from Stanley Park in Vancouver to High Park in Toronto to Mount Royal in Montreal) were created in that 40-year period (1880-1920).

This led to the first “street side plantings” – a new concept in post-industrial Canada. Trees were frequently transplanted from the nearby natural forest or from hastily constructed tree nurseries to supply the burgeoning municipalities. In time, these trees all had to be “managed” by the municipality. The question soon arose as to who would be responsible for managing these new “green assets”. Trees were treated like other infrastructure and their management was handed to those responsible for such things as roads, signs, and parking meters. When “asset management” developed into an entity onto its own, it was commonly associated with “grey infrastructure” (i.e., roads, signs, sewers), whereas trees and other “green infrastructure” were mostly overlooked as things that were just simply there to provide “some beauty” to the municipality. However, with recent municipal trends of greater cost accounting, the trend has returned to looking at trees once more as pieces of “infrastructure”, albeit “green” infrastructure.

Value of Trees to People

As Canada continued to urbanize (greater than 80 percent at present), trees increasingly rose in importance with greater emphasis on planting and maintenance to keep them on the landscape. Most of us are aware of the benefits of trees – they provide shade from the sun’s rays, they offer shelter and habitat for wildlife, they purify the air we breathe by taking in carbon dioxide and expelling oxygen, and so on. Less well-known is the fact that trees actually make us healthier, both physically and mentally. Trees block out unattractive views and noise while adding beauty to urban landscapes. Trees reduce heating and cooling costs by providing shade to homes in the summer and by buffering wind, ice, and snow in the winter.

Lately, the urban forest has been seen by many as a possible vehicle through which to reduce some of the impacts of climate change. The impact of the urban heat island on human health is currently receiving considerable attention in larger Canadian centres. For example, the City of Toronto passed a Shade Policy to ensure shade is now present after any new development or re-development in the city as protection against ultraviolet radiation and to mitigate the heat island effect – this includes natural shade (i.e., trees). The role of urban forests in reducing the effects of the urban heat island is well recognized. In its Climate Change Action Plan, the Quebec Ministry of Health recognized this role and announced a program of grants to help communities counter the heat island effect through re-vegetation.

Furthermore, other illnesses caused or aggravated by air pollution – notably respiratory illness, cardiac disease, and neurological pathologies (dementia, autism) – have negatively impacted Canadian populations. The Ontario Medical Association estimates more than 5,800 premature deaths per year can be directly attributable to air pollution. Trees and greens paces are widely seen as a way to mitigate this pollution.

Trees help combat Nature-Deficit Disorder, a condition that is becoming more and more prevalent among children today. Finally, the presence of urban trees and green spaces can contribute to the reduction of the prevalence and severity of several mental illnesses such as anxiety, depression, stress, and attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder in children, and improve general well-being by providing opportunities for exercise and social interactions. Indeed, the entire practice of “forest bathing”, widely developed in Japan to counter stress and other mental problems, is receiving greater acceptance elsewhere.

Many vulnerable populations live in districts deprived of trees and greens- paces. Based on available economic studies by TD Bank, it was shown that greener cities are saving billions of dollars per year in environmental costs through tree cover.

Values of “Green” Asset Management

Asset management planning is the process of making the best possible decisions regarding the building, operating, maintaining, renewing, replacing, and disposing of infrastructure assets. The objective of asset management from a municipal point of view is to maximize benefits, manage risk, and provide satisfactory levels of service to the public in a sustainable manner.

Traditionally, municipal assets were based on the “built environment” (also known as “grey infrastructure”): roads, sidewalks, sewers, storm water ponds, arenas, etc. The analyses applied looked at life expectancy and comparisons using various maintenance scenarios (e.g., no maintenance versus replacement in 20 years versus maintenance every five years, etc.).

Today, society has evolved to look beyond “grey infrastructure” and into “green infrastructure”. Green infrastructure is defined as the natural vegetative systems and technologies that collectively provide society with a multitude of economic, environmental, and social benefits. This includes:

- urban forests and woodlots,

- bioswales, engineered wetlands and stormwater ponds,

- wetlands, ravines, waterways and riparian zones,

- meadows and agricultural lands,

- green roofs and green walls,

- urban agriculture, and parks, gardens and grassed areas.

It also includes soil in volumes and qualities adequate to sustain and absorb water, as well as technologies like porous pavements, rain barrels, and cisterns, which are typically part of green infrastructure support systems. Green infrastructure is a system that extends from big city centres to rural areas. All components of the system are vital assets to our communities – but these assets may lack sustained funding and policy support from other orders of government.

Increasingly, municipalities are being asked to recognize and communicate the benefits provided by green infrastructure, including trees as a key component. In many analyses, green infrastructure has actually been proven to be a lower-cost solution to grey infrastructure and in some cases the two work closely together. Much of the research on this comes from the U.S. where for example, new guidelines for parking lots in California insist trees be integrated into the lot design to (in addition to many other reasons) prolong the lifecycle of the asphalt through the shade of the trees.

In Ontario, the entire management and accounting of municipal assets are provided for in O. Reg. 588/17: Asset Management Planning for Municipal Infrastructure – which sets out the minimum requirements for asset management. Recently, it has actually been changed to include green infrastructure in the scope of municipal assets. And so, municipalities that are preparing asset management plans must include green infrastructure (due by July 1, 2023).

Types of Green Infrastructure and Assets

In the municipal context, green infrastructure includes biological or living assets, such as:

- street or park trees as well as forests and woodlands,

- soils, and wetlands (including bioswales, engineered wetlands, and stormwater ponds).

In addition, it also has engineered assets, including: soil cells (networks of below-ground grey infrastructure, which supports sidewalks and curbs while affording trees adequate rooting space, etc.); rain gardens, engineered wetlands, bioswales, and stormwater ponds; and permeable paving (aggregate mixed with soil to permit trees to live).

Green Infrastructure

In evaluating and valuing trees, one must use the most appropriate and defensible method to value urban forest biological assets. At the Region of York, for example, this includes:

- Street trees, valued using the Council of Tree and Landscape Appraisers trunk formula method (as articulated by the International Society of Arboriculture);

- Shrubs and perennials, valued according to replacement cost;

- Growing media, valued at replacement cost;

- Ecosystem services (the many and varied benefits that humans freely gain from the natural environment, like oxygen production, CO capture, and stormwater detention), valued as derived from the United States Department of Agriculture’s (USDA’s) i-Tree Eco software analysis suite; and

- Civil assets, valued using depreciated replacement cost.

Additionally, the most appropriate and defensible method to value the York Regional Forest’s biological assets came down to the following criteria:

- forests, assigned timber value (as per recent timber sales in the York Regional Forest, which regularly cuts 2,400 metres cubed of wood each year to maintain its health), current land value, and the re-establishment costs of a new forest (site preparation, planting stock, planting, etc.);

- wetlands and prairies, assigned current land value, re-establishment (future);

- ecosystem services, assessed using the USDA i-Tree Eco software;

and - civil assets, valued using depreciated replacement cost.

Defining Levels of Service and Life Cycles

Part of asset management is identifying levels of service to be provided by green infrastructure – which is always a challenge. The level of service includes: community level of service; technical level of service; and performance measure.

Defining the life cycle for each type of living asset is another challenge. In York Region, the life cycle for street trees was defined by their three growing environments with an estimated average lifespan of: urban (35 years), suburban (44 years), and rural (53 years). Since the York Regional Forest is composed of natural forest communities, it was considered to be self perpetrating (with some maintenance) over time.

Green Infrastructure – Financial Strategy & Planning

Asset management should be the vehicle by which funding is appropriated and budgets are created. A funding plan puts asset management strategies into action, requiring investment to meet service levels.

From this, the municipality can predict key outcomes from its chosen financial strategy, its service levels, and return on investment for some treatments, and then decide on the need to establish a reserve to minimize impacts of funding peaks. The asset management plan then has to be put into action.

By bringing green infrastructure into the asset management system, a defensible approach to identifying investment requirements is introduced – thereby “leveling the playing field” with grey infrastructure. This in turn may lead to an increase in access to infrastructure funding programs (in which green infrastructure can provide a lower-cost solution than traditional grey infrastructure ever could).

Trees are the miracle municipal asset indeed. Count them in!